IN-DEPTH CONVERSATION WITH FURNITURE DESIGNER JINIL PARK

Eugene Metu-Onyeka

6 mins

IN-DEPTH CONVERSATION WITH FURNITURE DESIGNER JINIL PARK

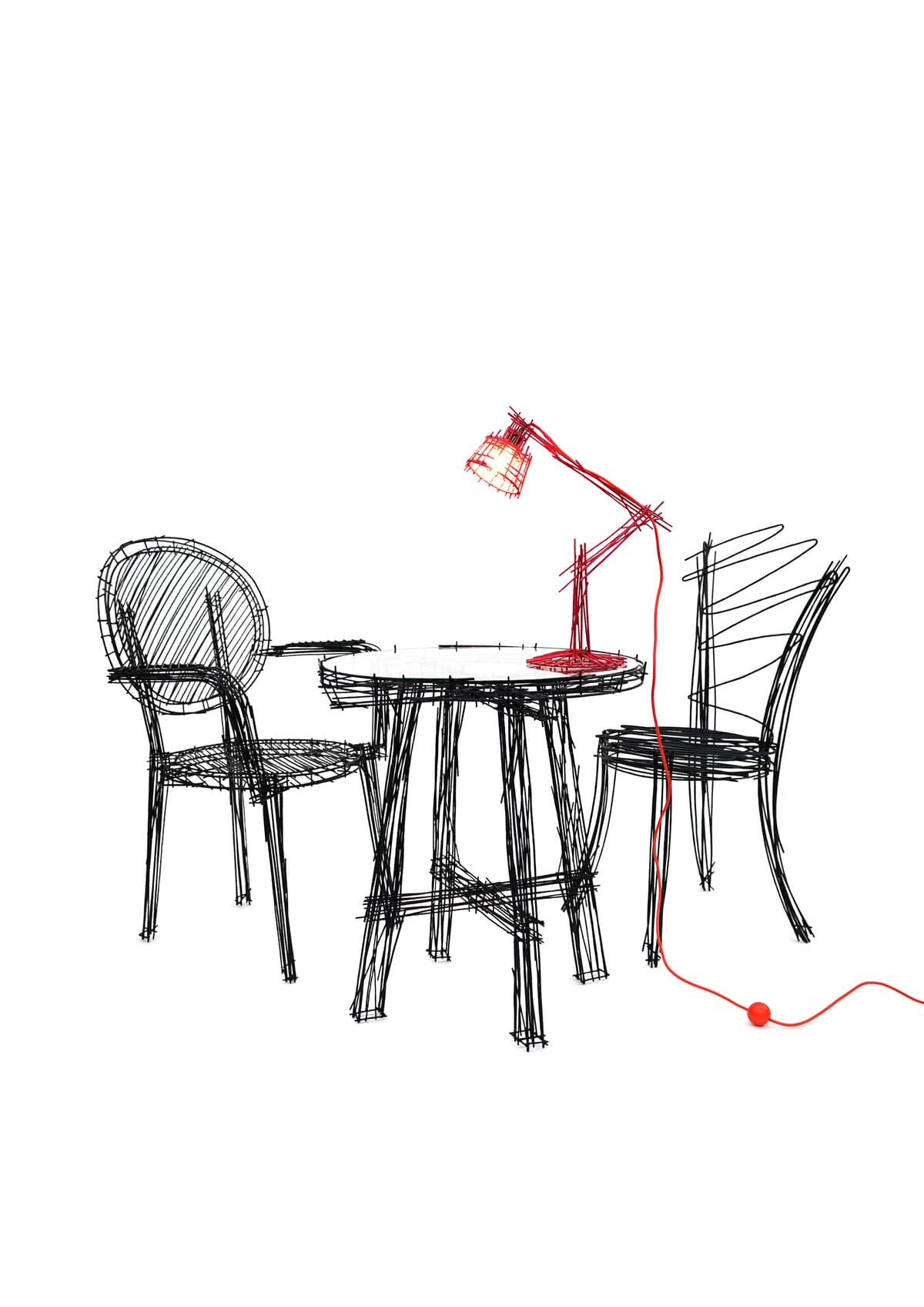

Jinil Park is a furniture designer whose creative journey is grounded in the simplicity of line and form. His work—an exploration of metal craft—transcends traditional design boundaries, blending the tactile with the emotional, the functional with the conceptual. Much like an artist starting with the most basic element, Park’s process begins with a line—an unassuming shape that evolves into complex sculptures that speak to both the practical and the expressive. In this interview, Park opens up about how his unique approach challenges the conventions of design, pushing the limits of creativity while embracing the beauty of imperfection. Through his work and teachings, he continues to inspire others to explore new dimensions of what design can be, encouraging a balance between artistic freedom and technical mastery.

Eugene Metu-Onyeka

6 mins

Eugene - Your process starts with drawing lines, which then become sculptures. How does this simple beginning help you express your bigger ideas about creativity? How do you think your work helps push creative boundaries?

Jinil - Just as every beginning is similar in its essence, when I first delved into the world of art, the very first step I took was practicing lines on a vast sheet of paper—like a baby taking its first steps. Then, as I entered an art college specialising in metal crafts, and gradually learned more about design and art, a sense of boredom crept in. That’s when I realised that breaking free from the confines of precise perspective and clean lines felt liberating. It was in that moment that I felt my creativity expand beyond its limits.

Eugene - The emotions you feel are important in your art, and you turn those feelings into shapes or structures. How do you think this changes the way we usually think about art? What do you want to show us about creativity through this?

Jinil - I don’t believe its vastly different from other forms of art. A painter expresses through canvas and brush, while I explore my own expression through the medium of metal craft, the discipline I’ve studied. My emotions are like the ebb and flow of the tide—sometimes calm, other times restless. And it’s in those moments of quiet or turbulence that I find my feelings emerging as lines, sculpted through the instant decisions of welding or the rhythmic strikes of a hammer.

Eugene - Turning a 2D drawing into a 3D sculpture is hard, but it also has a strong meaning. How do you see this process of 'bringing drawings to life' as a way to explore or change what creativity can be?

Jinil - Each person has their own way of expressing the creativity they carry within. For me, it was about bringing to life the doodles I’d drawn, turning them into something tangible. I wanted the drawings I created to transcend paper, to become something you could touch, something that served a simple, yet meaningful purpose.

Eugene - Wire is both natural and industrial at the same time. How does working with this material-bending, welding, shaping it - help you express things we often overlook in creativity? What does wire bring to your work about art, design, and function?

Jinil - Wire is a material that is both commonplace and inexpensive, yet remains a fundamental building block still used in countless industries. I believe the difference lies in how we choose to use it. Just as a simple stainless steel sheet may become a road sign in one place, or a sculptural piece by Anish Kapoor, or a chair by Ron Arad in another, the true value of a material is defined by the person who can reveal its captivating essence.

Eugene - You don't focus on making your work perfect. Each piece is unique because of this. How do you think letting things be imperfect challenges the idea that creativity must be controlled or polished? How does this help bring new ideas to life?

Jinil - There are already countless beautiful designs in the world—products with perfect proportions and finishes, crafted by designers far more skilled than I. So, I envisioned my personal works to carry a sense of freedom, a certain fluidity that sets them apart. Yet, the truth is, the works I create today are, to some extent, controlled. But this control is subtle—it’s focused on the parts of the piece where human hands will directly engage, where the tactile experience becomes most intimate.

Eugene - Your work is both strong in structure and emotional in feeling. How do you balance these two parts of your work—technical and emotional? How does this balance change how we think about creativity?

Jinil - At my core, I studied metal craft, a discipline rooted in the tradition of artisans creating beautiful yet functional works for everyday life. Sometimes, I feel as though my pieces express emotion in an intense way, but when I ask my friends, they often find it less overwhelming than I imagine. There’s always a balance, they say, where practicality and function still hold sway, even in the most expressive moments. I believe that point of balance is what gives the work it’s harmony.

Eugene - As a teacher at Hongik University, you help students explore different ways of creating. How do you encourage them to go beyond traditional ideas and think outside the box? How does this fit with your bigger vision of creativity?

Jinil - In class, my focus is on helping students develop the ideas they’ve conceived and guiding them through the technical aspects of bringing those ideas to life. Their minds are younger and more creative than mine, and I’m aware that my role isn’t to overshadow that, but to offer the benefit of my broader experience. When a student’s concept risks crossing a line—taking a direction that may not work as they intend—or when they face challenges in the process, I’m there to collaborate, to think through those obstacles together, and to offer support along the way.

Eugene - You choose designs that are not only beautiful but also practical. How do you choose what to make? Does the process ever surprise you in ways you didn't expect?

Jinil - I simply choose whatever I feel like creating that day. Some days I’m drawn to make a chair, other days it’s a light fixture. But once I start a piece, I tend to immerse myself in it for a week, or sometimes even a month, fully focused on bringing it to life. Lately, though, I’ve been approaching my work with a bit more caution, taking the time to consider each step more carefully.

Eugene - There’s a unique visual language in your work that feels both conceptual and tactile. How do you develop such distinct design elements, and what influences your aesthetic choices?

Jinil - I do not challenge the definition of art and design. What I do simply exists on the borders. It involves a labor-intensive, craft-centred process, offering visual delight through its outcome. It’s a piece that serves a modest function, a sculpture of sorts—not a work laden with profound meaning. I simply find joy in the act of creation itself.

Eugene - What advice would you give to emerging designers who are looking to create meaningful, innovative work in a field that’s becoming increasingly saturated with digital noise?

Jinil - If you are in an environment where you can utilize advancing digital technology, I hope you actively adopt and take the lead in applying new technologies to explore creative work. Technological advancements have brought significant changes to art and design, and I believe we are currently in a crucial transitional period.

However, if your inclination is more towards traditional craftsmanship, like myself, working with metal and focusing on handcrafting, then first and foremost, do not give up. Always observe your surroundings carefully and practice perceiving brief moments from a different perspective. Over time, you will encounter moments that inspire you, and I believe this will eventually lead you to create meaningful work.